|

Promiscuous Affections A Life in The Bar, 1969-2000

1996-1999:

|

|

Anecdotal "facts"

|

Sex

Policing desire, playing politics, pushing pills

The Sex Police were ever diligent, latching onto even the slightest evidence that might serve to indict our erotic repertoire.

In 1994, six years after the Canadian AIDS Society's Safer Sex Guidelines first appeared -- and just months after research for its second edition confirmed that cocksucking was low risk -- Out touted on its cover "FACTS About Oral Risk for HIV."

That led to a big feature called "Watch Your Mouth," under the title: "The word is in on HIV and oral sex, and it isn't good." Its author was Gabriel Rotello, who had clearly studied at the Randy Shilts School of Hollywood Journalism.

- The mood inside the Columbia University auditorium on a recent Saturday afternoon was heavy with a sense of fears confirmed. The topic at hand was AIDS. ... "I came here with a close friend who doesn't want to stand up," he [a "respected 40 year old AIDS treatment activist" -- unnamed] began. "For the last 12 years my friend has not had any sex other than receptive oral sex. And never to the point of ejaculation. Three months ago he seroconverted."

Now the room was almost electrically quiet.

Rotello also gave us "well known New York activist" Steve Quester, who said that after years of testing HIV negative he had "engaged in three instances of unprotected sucking to ejaculation" and was now positive. Quester was pictured as a "case study," his face pathetic, accusatory.

Rotello cited the few epidemiological studies that had indicated infection via oral sex -- almost all complicated by the fact that people don't always tell the truth about sex -- but preferred those "individual case studies [that] document the human face of the issue. There are now dozens of such studies."

Dozens. Out of millions with HIV.

"A sense of fears confirmed," he'd said: fears coming first -- eager to be confirmed by "facts." No surprise that a US historian once wrote of American politics' "paranoid style." I'm reminded of another line I got from Jane Rule: "The fear is worse than the fact."

***

Listening to Americans go on about cocksucking is like listening to them debate health care. Ideological blinkers blind them to a sane model -- public, portable, universal, cheap or even free; less costly overall than US corporate medicine (if now getting mucked up by budget cuts and creeping privatization) -- just north of their border. In fact in much of the world.

When noted at all it's most often as a bogeyman: "creeping socialism." Rotello did report that "The Canadian government [sic], it's said on the street, considers oral sex safe" -- a "rumor" he investigated no further.

Grim doc: Seven suspect cases get a pg 1 grabber in Xtra West. |

"Now the guidelines will have to change. 'On me, not in me'

is a very wise guideline."

-- Wisdom from

a Vancouver dentist.

But lest we get smug: on September 9, 1994, the page 1lead on Vancouver's Xtra West read: "Receptive oral sex risk." Dr Joss De Wet had, as the caption to his sober face read, "four men in his practice who now test positive after engaging in what the Canadian AIDS Society classifies as low risk activity." He said he knew of three more.

A local dentist seeing people with HIV said: "Now the guidelines will have to change. 'On me, not in me' is a very wise guideline." It its September 16 issue, Toronto's Xtra lifted the story, if on page 13, heading it: "Seven claim HIV infection after oral sex."

Two weeks later in Xtra, ACT's John Maxwell was quoted: "Out's 'latest facts' are old news. We've never said oral sex is completely safe. Low risk doesn't mean no risk."

I wrote that article, based on an interview with John and with Brent Allan of CAS. I asked them: "So why not say, 'Don't do it'? One of the men in Vancouver urged, 'use a condom -- oral sex, anal sex -- it doesn't matter.' Does it matter?" "It matters a lot. Fucking without a rubber is much more dangerous than sucking cock," John said, "condom or no condom."

Brent added, "In the US they've said: Don't have any unprotected oral sex. But most people just won't suck latex. So they do it without a rubber and think, oh God, that's it, I'm dead now. Why bother with condoms anymore? Advice meant to save lives could have just the opposite effect."

For instance: "On me, not in me" -- so usefully specific. We may as well go back to fear of "bodily fluids."

***

Knowledge = Life: Banner of an ACT ad I did for Pride Day, 1992. |

"When AIDS began the world tried to stop it with one word: No. But our community found a better word: Know.

"Know. Knowledge is the key to action. And Action = Life."

My questions were disingenuous: I was not being an "objective" reporter but, with Brent and John, an AIDS activist using Xtra as a political tool to confront the latest Sex Panic.

That article, the first of four I did, reiterated the Safer Sex Guidelines, saying "The Canadian AIDS Society doesn't say do this, don't do that. They say: Know. And then it's up to you."

In the second piece John and Brent talked about the difference between "risk elimination" strategies -- big on orders meant to ensure absolute safety (if followed) -- and "risk reduction" based on informed choice.

"If I take away your right to choose," Brent said, "how good do you feel about it? You have to look at a person's total health, not just risk of disease. People get anxious when they face risk, but it's even worse when they can't take any control for themselves. That's when you really get stressed. And that's lousy for your health."

My third piece was on "The Dam Debate." Rotello had said in Out: "For lesbians, unfortunately, there's little that can be done to minimize the obtrusiveness of dental dams." Lesli Gaynor of ACT and Dionne Falconer, director of the Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention, knew what to do with dams -- ditch them if you want. Both saw dental dams as a kind of techno fix, even a bid for safe sex solidarity: if the boys need latex, we do too.

"Why," I asked them, "have lesbians -- the people with the lowest incidence of HIV infection -- been talking about an uncomfortable piece of rubber that's hard to find outside a dentist's office?"

Because, they said, it was the safest thing to talk about. "It's only okay to talk about oral sex," Lesli said, "so lesbian sex is oral sex, period" -- leaving aside things more scary and potentially more risky: fisting, or sex toys. Or sex with men.

"The bottom line for an educator," said Lesli, "is that you provide as many choices as possible, from unprotected, go for it oral sex to no oral sex. You have to make those choices for yourself. That's important to health, both emotional and physical health."

***

|

Take control

|

Options, choices, taking control for yourself -- all based on health promotion rooted in community.

"Erring on the safe side," Walt Odets wrote, meant "not only withholding information from gay men but lying to them. ... Such education is not a prescription for AIDS prevention, it is a prescription for madness."

ACT's new campaign to reach young gay men, produced by John Maxwell, launched in March 1995 and called Go Deeper Into Safer Sex, featured a pocket sized brochure backed up by four different postcards, all distributed in gay venues (images on them shot in gay venues).

Each card highlighted one of the campaign's four themes: Get the facts (still, if simply stated); Discover the options; Make choices; Take control. The very last line in the brochure: "Because you ARE worth it!" I was glad to see that, a variant on what had come to me years before at The Barn, watching men dance: "I'm worth it." (But soon that signified hair colour by L'Oreal.)

Options, choices, people taking control for themselves. John, Brent, Lesli and Dionne all talked about that -- all based on their knowledge of health promotion and community action.

It was a concept still foreign to many. Brent Allan, mentioning it at an American Physicians for Human Rights confab in Texas, was asked: "What's that? Some kind of socialized medicine?"

Well in fact, yes: health care rooted in a social context, practical advice people can put to work in their own lives -- not "Do what we say or you die."

About that authoritarian approach, common early on even in Canada, Dionne Falconer said in our interview: "Whose ideology were we playing into with that?" Nancy Reagan's maybe: Just say no. Or Margaret Thatcher's. I'd write in the last of these articles (on which more later):

- Sex advice is never objective, never just "facts." It comes weighted with ideology, hidden assumptions about sex and about our relations with each other.

The idea of 100 percent risk elimination comes from a culture of fear. If there's a threat out there, avoid it, contain it -- maybe even destroy it. At what cost to society? Who cares! As Margaret Thatcher once said: There is no society, there are only individuals.

Coping with AIDS isn't just about protecting yourself. You don't live your life by yourself. It's about building communities of mutual learning and support. That is the real work we have to do.

***

It was, thankfully, an American who blew the whistle on the Sex Police. In the Spring 1994 issue of AIDS and Public Policy Walt Odets, a clinical psychologist from California, wrote a piece called "AIDS Education and Harm Reduction for Gay Men." In May 1995 it was excerpted in Harper's magazine, titled there "The Fatal Mistakes of AIDS Education."

- The primary tactic of educators has been to provide people with sensible information and, for those not persuaded by good sense alone, to coerce behavioral change by the power of social compliance.

...efforts have been marked by misrepresentations -- not only withholding information from gay men but lying to them. As with most attempts to mislead people, when the misrepresentations are finally discovered, the useful components of the message will be discarded along with the untruths.

Most of the misrepresentations of AIDS education have taken the form of "erring on the safe side," an approach that often makes the entire prevention message seem an impossibility.

Many gay men experience protected sex as restrictive, inadequate, or unacceptable. By hiding this reality behind slogans like "100 percent safe, 100 percent of the time," we force the issue into the closet. There, like closeted homosexuality itself, the practice of unprotected sex develops a secret life with immense potential for destructiveness.

That sounded familiar, at least north of the border. I wish I'd had the nerve to say that "better safe than sorry" in fact constituted a lie -- one that some of us, even here (even I), had perpetrated on our own people.

***

Johnny talks temptation: "Would you have sex with this guy without a condom?" |

"It isn't about saying: Here's a discussion group you can come to. It's going out at three in the morning with a bunch of guys from Colby's."

My final anti panic piece ran in Xtra, March 3, 1995, titled: "On Latex, Secrets and Silence: Why are we afraid to talk about unsafe sex?"

It had a photo of John Maxwell holding up an ad he'd designed and run in Xtra in late 1994: a hunky torso with the caption, "Would you have sex with this guy without a condom?" And then below, smaller: "If so, you're not the only one." It was meant to attract gay men to a discussion group. Just four showed up.

"So the first thing we talked about," John said, "was exactly that. Why did those four men think they were the only ones there? 'Well, come on,' they said, 'it was an invitation to admit you've had unsafe sex. Who's willing to do that? And who do you want to hear it? Some stranger who might point you out later in a bar?'"

They were right. We'd set such impossible standards -- as if a community of humans were a company of angels -- that if you failed them, John said, "you feel like a write off, a piece of shit."

"Think of the traditional ways we tried to get the message out," he said,"-- posters, brochures -- people are really tired of that. It's bad news. And it's boring. The point isn't for me, white middle class John Maxwell of ACT, to tell people what to do. It's for them to connect with each other and support each other."

That might have seemed to herald the rebirth of Talking Sex, ACT's faciliated yak fests of 1988. It did not. It reflected instead the work of the Gay Men's Education Network -- done not by one group but many, not in isolated workshops but out in many, varied communities.

As John noted, "it isn't about saying: Here's a discussion group you can come to. It's going out at three o'clock in the morning with a bunch of guys from Colby's."

I wrote there: "We can all do that: Talk. In bars and baths, on the street, at home. We know our own sex lives and we're our own best educators. But we can't do this work if we're afraid to talk -- afraid that we'll become pariahs if we tell; afraid that if we're told we'll have nothing to offer but embarrassed avoidance or a stern lecture, no guide but our own fear."

***

After finishing this site, I found another insightful American take on the impact of bad "safe sex" psychology on the psychic health of our communities, in two books by Eric Rofes: Reviving the Tribe: Regenerating Gay Men's Sexuality & Culture in the Ongoing Epidemic; & Dry Bones Breathe: Gay Men Creating Post- AIDS Identities & Cultures (Harrington Park Press, 1996 & 1998).

See online a review of Reviving the Tribe

(www.thebody.com/

shernoff/rofesrev.html)

Odets said "the most sacrosanct expression" of the "all safe sex all the time" approach was "the absolute prohibition against saying that when neither partner has HIV, it is acceptable to have anal sex without a condom."

He also criticized routine HIV testing as a way to "make a man behave 'more responsibly' if he knows he is positive" -- even as we urged gay men always to act as if they were positive.

"We have 'double bound' men into such confusions," he wrote, "with a remarkable show of bad psychology which says in effect":

- Get tested and believe your results. (But if your test is negative, don't believe your results: use a condom anyway.) Safe sex affirms your pride in being gay, and loving gay men protect their partners (from what?). But don't trust your "monogamous" partner (gay men lie and cheat). Feel good about sex: It's natural and it's your right. (But get tested again in six months to see if you've finally gotten yourself into trouble.)

"Such education," Odets wrote, "is not a prescription for AIDS prevention, it is a prescription for madness. New approaches must tell the truth about these issues, must acknowledge that it is sometimes quite 'safe' to have ordinary, unprotected sex, and must help men develop a sense of judgment that would allow them to make the best decisions based on their values and their appraisals of acceptable risk."

***

"I can relate:" Open talk can keep relationships strong & safe -- maybe even without rubbers. |

"Negotiated safety" made AIDS absolutists quake, an "admission" opening the door to danger. One educator said: "Men need to be told what to do."

Mostly so he could say:

I told you so.

In "The Prophylactic Lover," in TBP, May 1986, I had been among those advising suspicion of one's "monogamous" partner. They are (as I learned from Barry's lover Randy) expected to lie and cheat -- just as husbands are.

In late 1997 ACT released a brochure called I Can Relate, meant specifically for men in couples. It didn't avoid the issue of trust. It said, as I had then, that there is no magic safety in "love." But it also said that the point wasn't simply trust. It was communication -- even if not always easy:

- Do you know your HIV status? Are you prepared to get an HIV test? [Does your partner? And is he?] Are you [or your partner] having sex with people outside your relationship? Are you [and he] having safer sex with these people? Can you [and he] talk openly and honestly about sex outside your relationship? Would you be able to talk openly with your partner if you did something that put you at risk?

If the answers were "no," then even "monogamous" couples should use condoms. But if they were "yes" -- and both partners knew they were HIV negative -- they need not. Why should they?

But what came to be called "negotiated safety" made many AIDS absolutists quake, saying, Walt Odets wrote, that "such an 'admission' would encourage men to do dangerous things." A man working with the San Francisco AIDS Foundation said to Odets: "Directive education is necessary because men need to be told what to do."

The real need there was that educator's (and so many others' in the "helping professions"): need for the rush of smug sanctimony that comes from telling other people what to do -- whether they do what they're told or not.

Public consequences -- coming later, often out of sight -- pale in the glow of instant gratification: the private, self satisfied nobility that lets one sigh, "Well... I did my best."

***

Bareback bandwagon: Xtra riding it (image by Maurice Vellecoop) in an Aug 1998 piece a tad prone to the "shocking." |

"For some of us, there is a peculiar, bittersweet liberation in becoming HIV positive, a double edged sword that slices away the anxiety & hard work of staying negative, but forces one to face mortality."

"Some older queers gasp at hearing these feelings."

-- Tony Valenzuela

in a more thoughtful take,

Xtra, April 1999.

Many who weren't doing as they were told were in time willing, even eager, to talk about it.

Xtra's August 13, 1998 cover carried the draw: "Riding bareback: Unprotected sex comes out of the closet." The article dealt with Internet chat groups and mailing lists of people actively seeking unsafe sex.

- The content focusses on the eroticization of transmitting HIV. The heading of each page [of the Xtremesex website] features a slogan defining the audience: "for poz hungry men into bareback sex." Some refer to HIV as "the gift." Positive guys are called "gift givers." Guys who want to seroconvert are "bug chasers."

The media loved "barebacking" -- as they do "road rage," "kiddie porn," "terrorism" -- complex social phenomena made buzzwords fit for big headlines and snappy soundbites. Space, time -- they're the usual self created, self absolving constraints of "journalism." "It's too long! It won't fit!" Public discourse is left to feed on bite sized nuggets of shit.

And now, as was also their wont, they could blame it all on fuck crazed fags. When they wanted a term more authoritative they were thrilled to find "recidivism" -- borrowed from criminology. Like any parolee who makes it to the headlines or the top of TV news, we had "offended" yet again.

***

John Maxwell's take on "barebacking" was more nuanced. "It depends," he told me, "on what people mean by it. What a lot of people call 'barebacking' is just ordinary, everyday unsafe sex." That is: it happens, as it has always happened.

In Men's Survey '90 (the study that failed to get gay men's take on cocksucking because a few anonymous sexperts didn't know what to think of it), more than 20 percent of respondents said they'd had unprotected anal sex at least once in the three months prior, more than a third in the last year.

But -- typically for such arm's length, "quantitative" research, satisfied with statistics devoid of social context -- it did not ask what that meant to those men.

Did they try to have safer sex but sometimes slip up? Just once? Many times? And most importantly: Why? Booze? Drugs? Desire beyond control?

Or did they actually mean to do it? As John saw it, in conscious "barebacking" -- the real thing replete with meaning, not mere media hype -- they do.

Some said this unleashed desire grew from a sense of reduced risk: there's "the cocktail" after all (my least favourite bit of media hype: this is a party?); people are living much longer. Xtra's Proud Lives compendium for 1993 had shown us 187 dead; for 1998 there were 25. That might explain more casual unsafe sex, but likely not its intentional practice.

***

Some real thought on the topic showed up in Xtra's April 22, 1999 issue: an essay by Los Angeles activist Tony Valenzuela, called "Barebacking is a Cherished Act."

He derided that act being "fallaciously reduced to the premeditated act of HIV transmission without concern for oneself or others." Yet sometimes it is premeditated, even, as Tony said, cherished. Its motives were not beyond his comprehension.

- Four years ago, I tested HIV positive. I was 26 years old. Strangely, it felt like a relief. The moment I learned my new status I felt freed of the angst that consumed my adolescence and young adulthood with fear and dread of infection.

Some older queers gasp at hearing these feelings, though they're not uncommon among my peers. For some of us, there is a peculiar, bittersweet liberation in becoming HIV positive, a double edged sword that slices away the anxiety and hard work of staying negative, but forces one to face mortality.

Older queers gasped indeed, old AIDS activists most loudly. Bob Tivey, whose career has taken him from Vancouver to a job with Toronto's public health department, wrote to Xtra:

- For Tony Valenzuela to argue that being HIV positive and having peace of mind is preferable to worry and concern about being disease free is totally bizarre and frightening to me. ... The politics of HIV are out of whack.

Stop the world, I want to get off.

***

Sorry dear: the world won't stop. And I for one don't want to get off. Nor do I find what Tony said in the least bizarre.

As HIV politics it's no more frightening in its potential effects than AIDS prevention advice that long ignored the profound power of sex, its meaning beyond mechanics; that smugly ordered us not to do what -- everyone knew -- we deeply desired and might do nonetheless.

I'm not surprised that some people could find sex worth dying for. Some would no doubt say I am going to die for it, though I haven't actively chosen to. But even Jeremiahs are forced to face mortality. Everyone is: death is inevitable.

Living is not. It takes work, facing messy contradictions, tough choices, big risks. Perhaps the biggest -- if great literature can be our guide -- is the risk that you may reach death without ever having lived the life you so much hoped to.

Near the end of his article Walt Odets wrote: "AIDS education must re- evaluate its fundamental purposes. We are not addressing the human needs of the gay community by offering or insisting upon biological survival as the exclusive purpose of human life.

"Lives must be worth living."

***

I once saw Terell Cress take a list of "The 10 Characteristics of Longterm Survivors" down from a wall & amend it, resisting prescription with a single word: "Some."

In my own AIDS career, as an activist but more so as a person with HIV, I have always cared less for a long life than a life worth living. I didn't want AIDS to become my life, a disease the only definition I'd be allowed. Or worse: want.

At ACT I met walking encyclopedias of epidemiology, infectious disease, every detail of every new drug, every available (or so far unavailable) alternative therapy. I applauded their diligence: it would have tremendous impact on the medical establishment. But I hoped to avoid what seemed for some a total obsession. They could act as if nothing else in life were worth their attention.

I also saw men with HIV grasp that virus as an identity beyond all others. Some liked the label "Survivor." I hated it, knowing it was most richly uttered, or heard, with a slight catch in the throat -- the sound of a Survivor's "brave" self sanctification; the "concerned" seronegative guilt of those around him.

In 1990 I attended a "Survivors' Group," men with HIV working at ACT and the PWA Foundation. I found there that group therapy (the clear model) meant gut spilling, calm thought a sure sign of "repression"; that the "script" was pre- written by the facilitators; that what we did was secret -- ostensibly to protect confidentiality but really to make "group" our sole salvation, the only place we could really "talk it out."

I detested every minute of it, staying on only out of commitment to those men I worked with. I missed three sessions: for Michael Wade's death, his memorial and, a few weeks later, Peter Day's memorial. I learned far more living through those events -- out in life, even if about death -- than I ever did in "group."

Terrell Cress once took down from a wall in AIDSupport a sheet headed "The Ten Characteristics of Longterm Survivors," resisting prescription by amending it with a single word: Some Longterm Survivors.

***

But is there any such thing as "AIDS alone"?

I also saw some People Living With HIV (upper case relevant here) use their status to gain not social pity but (if still guilt induced) political power.

I applaud that power, too, just as I do the power of any people who come together in common cause and rise up to seek justice. But I do not applaud either its viral excuse or, at least in one case, its true motive.

In late 1993 ACT's board of directors issued a statement called "Who Own AIDS?" ACT's former director Stephen Manning had asked the same question in an address at the Canadian AIDS Society annual meeting in 1990, printed in Xtra that summer as "Owning AIDS."

"Owning an issue," Stephen said, "means having the moral right to speak about it and to be listened to, to have a say in how an issue is represented and what it really means." He saw such moral ownership as "the proper business of communities: networks of mutual belonging, visible identity and common fate."

"AIDS cannot belong to people for whom it is only a professional problem," he said. It must belong to communities who face it directly, who are deeply involved in confronting it. And that was, Stephen concluded, "the gay communities of Canada."

Stephen spoke against a trend of the time: the "degaying" of AIDS; the drift of "AIDS service organizations" from community roots to "professional" control.

In 1993 ACT's board quoted his rationale but came up with quite a different answer: "We believe it is time to recognize a stronger claim than that of the gay and lesbian community -- the claim of all people actually infected with HIV."

ACT had always worked with people infected with or affected by HIV and AIDS. Now the board wanted to focus on the infected alone.

***

This noble call to heed the voices of PWAs was in fact an attempt to suppress other voices, as the board said: "voices speaking not only of gay and lesbian issues but of issues even broader and further from the fact of AIDS." They said ACT's only issues should be those of "AIDS, and AIDS alone."

Those "other voices" belonged to, among others, ACT's own gay, lesbian and mostly HIV negative staff -- who had "won" against the mostly HIV positive board in that year's big Bob mess. Most grating to some ears were the voices of uppity activist dykes who saw every issue as, at heart, a political issue.

The board cited "straight women, the fastest growing infected group," saying they didn't "see themselves reflected" at ACT -- ignoring the work of those very dykes in the Women and AIDS Project, that work taken out into various communities -- where it belonged. The board fixated instead on "direct service" -- the kind people had to come to ACT to "access."

They were also banking on an old myth: "AIDS is not a gay disease" -- or not so much as it had been. They knew it was a myth, if a usefully pervasive one, rising mostly from American experience -- which thanks to the media is pervasive indeed.

I used an Xtra phone poll (hardly scientific, but suggestive) to show just how pervasive it was, asking readers what percentage of people living with HIV or AIDS in Toronto they thought were gay men. Most said 50 percent or less. In fact (best I could tell from statistics then), it was more like 85 percent.

***

In Xtra's January 21, 1994 number I did an article titled with the true issue here -- "Who Owns ACT?"

- "Our focus is AIDS, and AIDS alone" [the board had said]. But is there any such thing as "AIDS alone"?

To say that AIDS is not about poverty, discrimination -- even about life in our bars and bedrooms -- is to say that AIDS is not part of the real world. AIDS is unavoidably political.

Not all of us infected with HIV are gay. But most of us here are. Not every AIDS organization should be gay. [I cited local ones that were not.] But some must be. We built ACT. We made it a place where being gay was not only okay but the norm. We could say it was ours. Now some say ACT should not be ours.

Instead it should be a neutral agency where professionals serve people with HIV, defined by a virus, not by who they really are.

That means it will belong to no one -- but the professions. [Chief among them then the board's chosen instrument to cure staff of messy "politics": Carol Yaworski.]

I said there: "When you find out you're HIV positive, you aren't lifted from the world you knew into some mythical 'HIV/AIDS community.' " But some felt they were.

The chair of ACT's board then -- a handsome young A- gay lawyer much out on the scene, and a Person Living With HIV -- once said he had more in common with a seropositive single mother than with other gay men.

I wanted to ask him (though never did) when he had last invited a welfare mom and her kids in for an elegant Sunday brunch.

***

It wasn't just HIV that got "hit fast, hit hard." It was human bodies, whole lives -- treated like viral test tubes.

AIDS politics, particularly HIV Identity Politics, are blessedly behind me, AIDS now simply life's background.

And that background, mostly, is drugs.

I did Pentamidine for just two years, replacing it with Septra, an oral sulfa drug many people couldn't tolerate. I could and I'm on it still. I took AZT for nearly 10 years (with ample evidence of its muscle wasting effects: I have no butt), adding 3TC in 1996.

Both drugs, along with ddC, ddI, d4T -- etc; a whole alphabet soup -- are nucleoside analogues that interfere with one stage of HIV replication. Later that year we saw the advent of protease inhibitors that interrupt a different stage. Combining drugs had long been advised, but only with the newest ones did we get "the cocktail": various mixes of protease inhibitors and nucleoside analogues.

So -- have a cocktail! (So chic! So now!) If it doesn't work -- try a different mix. Or another. It became "clinical wisdom" to advise swapping brands often, to hit HIV from lots of angles -- to "hit fast and hit hard." By 1997 some AIDS specialists were avidly inviting us to the party, goods supplied by big drug firms, the media of course doing "cocktail" promo.

Only later did anyone say much about side effects -- which a friend once said should be called simply "effects," some intended, some not, some completely unanticipated. I'm now on a drug to improve my fine motor control, often not so fine; it was first used for angina but to everyone's surprise also helps stop the shakes. That's nice. But rashes, vomiting, kidney stones, pancreatitis, peripheral neuropathy -- they're not.

Nor, until studies on "non-compliance" were done was much made of how hard it could be to "comply" with these regimes: many doses a day at specific times; some on an empty stomach, some with a high fat snack; some conflicting with other drugs and even with each other.

And even after all that -- one combination, then another, maybe yet another -- the virus might resist them all, the cocktail bar having no new mixes on offer.

***

It wasn't just HIV that got "hit hard." It was people's entire bodies, their whole lives. Too many doctors could forget they weren't treating a virus in a test tube, but human beings who have to live in the real world.

And, finally, in most cocktail hype we rarely heard what it might cost -- not to the body but the wallet. I didn't start 3TC until I knew I qualified for Ontario's Trillium Drug Program, set up to help people with high drug costs relative to their income.

It began under the NDP government, pushed by AIDS Action Now! -- who were smart enough to press for coverage of all drugs, not just AIDS ones. Other provinces have similar plans. Most people in the US without private insurance aren't so lucky.

Still, I thought long and hard about dumping new chemicals into my body. I feared their effects, hated the hype, the desperation of those who said "I'll do anything to save my life!" -- hated most their greedy sense of entitlement to benefits others can't afford or even imagine.

My doctor Philip Berger didn't push: he hates most of the same things I do. But by February 1998, my T cell count dropping and my viral load rising (actual virus levels now measurable), I gave in. Since then I've been on 3TC, d4T, and Indinavir -- a protease inhibitor trade named Crixivan.

That one did have unintended effects if, oddly, long after I started it: in July I threw up almost every day for two weeks. I lost 15 pounds. I've gained them back, if not quite as I might hope. One of Indinavir's unanticipated effects is redistribution of body fat from the extremities to the gut and upper back: "Crix hump"; "Crix belly." My jeans are getting tight.

But all this is trivial. I feel fine if I get enough sleep; I'm not too busy to plan my meals around pills. I go get them every month, coming back from the Wellesley Drug Store carrying what I paid just $6 for in dispensing fees.

Still, I can feel like a Brinks truck: their full price, the receipts tell me, is $1,091.14.

***

|

Pushers in the ghetto

|

Often on the way I pass a billboard painted on the side of a building (right across Church Street from The Barn; it briefly housed a bar called The Manhole).

It's an ad for the Community AIDS Treatment Information Exchange, CATIE, an AIDS Action Now! spin off that won a federal contract to run a national AIDS treatment info service -- after the feds' first choice, a big Montreal hospital, blew the job.

"Living with HIV," it reads. "Get the facts. Know your options." We're shown what we look like: two nice couples, male / male and male / female; a mother with child; a man who looks Asian (or native); one Black; and one rather scruffy (maybe meant as a junkie). One man stands alone, three storeys tall, one hand out palm up as if instructing, or imploring. They all look terribly earnest.

Across the bottom are the sponsors' logos: Glaxo Wellcome (AZT); BioChem Pharma (3TC); Bristol- Myers Squibb (d4T); Merck Frosst (Crixivan); and CTAC, the Canadian Treatment Advocates Council. CATIE is community based, careful in its advice not to be a flack for drug companies. But heaven knows it needs the money those ad sponsors bring.

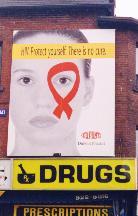

Later I saw another ad, on bus shelters, on the backs of Xtra, fab, even the Pride program. It's for DuPont Pharma, the chemical giant's local branch plant, promoting its new AIDS drug, Sustiva. (If not by name; I don't think they're allowed to. But that's fine with them, the message: "DuPont will save you.")

On July 10, 1999 The Globe and Mail reported a protest in Ottawa, by CTAC against government approval not of Sustiva but of its price -- "up to 40 percent more than what other companies are charging for products that work in a similar way."

But all that's old news, really. More surprising is that the ad is too: a glamorous young woman with a solemn stare, one eye looking through a looped red ribbon (that ubiquitous, trendy symbol of "AIDS awareness"). Its banner, black on yellow, colours of warning: "HIV. Protect yourself. There is no cure."

I can't help recalling those City of Toronto bus shelter ads from 1987: the same Meaningfully Serious Look, "Avoid AIDS" then, "Protect yourself" now.

Just "yourself"?

Well, I don't really expect a drug company -- even as it plasters its promo all over the ghetto -- to know piss all about community.

***

Wandering my neighbourhood, which in less thoughtful moments I can take for my entire community, I can find odd its drug ad saturation. Kevin Orr would find it odder still, were he here to see it.

He's not often now, if not forgotten. Last July I got to stand in for him, at the hotel that used to be The Carriage House, the Ontario AIDS Network meeting there to induct people to its Honour Roll, Kevin among them.

I saw Yvette Perreault and Ed Jackson, both similarly honoured, as were Stephen Manning and Michael Lynch -- also in absentia, Eddie accepting for them. (Stephen, born and raised American -- geographically speaking -- is now in San Francisco.)

Not there were Bob Martel, Carol Yaworski, or any of ACT's board from 1993. A nice irony: honours for the renegades, the "professionals" forgotten. I felt again as if I'd come home -- to AIDS activism at its best. (In September 1999 I was added to that Honour Roll myself, along with Robert Trow, whose community health work with Hassle Free Clinic goes back to 1976.)

Accepting Kevin's honour, I said he was likely in Morocco. He has worked for some years now with the International HIV/AIDS Association, based in London but sending him all over the place: Burkina Faso, Bangladesh, Senegal, Sri Lanka.

In the communities Kev sees now, if the cure for AIDS were no more than clean water, most people couldn't get it. He moves among many distinct cultures, so different he can't presume to know them well, certainly not so deeply as we knew (some of) gay male culture when we were in it together, facing AIDS.

A while ago on the phone (he usually calls when back from a night out in some London bar) I asked him about that. Is it difficult? I didn't record exactly what he said, but basically it was this:

Yes -- but not in ways entirely new. It's still about working with communities, with values and customs one must respect; about helping people take what power they can, in the simplest and most practical ways, to improve their own lives and the life of their community.

He's told me tales about what pains some of the "professionals" can be, some governments of course, too. But none of that's new, either. "Mostly," he said, "I have to listen, hear the people there talk it through. I can help, but they're the ones who have to figure out what they can do."

***

We insisted our bodies are not machines, our sexuality not mere plumbing. We learned our health depends on the health & strength of our communities.

None of that should we, or the world, ever want to give up. Not even to be free of AIDS.

There was once a poster up in ACT's Access Centre, showing the entire globe. Over it were the words: "Be Here for the Cure." I never liked it: I probably wouldn't "be here"; neither would too many others I once knew, even some I knew still.

Later there was another, a sign often carried on Pride Day: "All I Want is a Cure -- and My Friends Back." That one I positively hated (so did Gerald Hannon: "When I see that up anywhere I want to go tear it down. 'Me! Me! Me! It's all about Me!' ")

What I most objected to in both was the sense that one could go back -- and want to -- if not to one's friends then back to the world just like it was before AIDS.

Well, I don't want to go back to the world just like it was. I want much more than a "Cure." I want all that we've learned from AIDS to stay in the world long after AIDS is gone.

I once had to see a specialist, a gastroenterologist, referred to him by Philip Berger. His name was Gabor Kandel, Hungarian, so I imagined rather conservative (anti Communist at least). He turned out engaging, progressive, and a very good doctor.

He once said to me something I've never forgot, in essence this: I have never seen a group of patients so well informed, so clear about making their own decisions, as people with HIV and AIDS. He liked that.

Philip recently told me about being at an AIDS conference in 1988, for doctors only but "the one and only" Chuck Grochmal had got in. Feeling ignored, a mere PWA in this crowd of health professionals, he shouted: "We have the power to CRUSH any clinical trial in this country!" -- punctuating "crush" with a slam of his fist.

The room went silent, Philip said, sensing a power doctors rarely have to face.

***

That power is the positive legacy of all those walking encyclopedia PWAs. And of much more.

Women working together for each others' health since the 1970s, knowing they knew their own bodies in ways few doctors could, sharing (then and still) what they knew in a book called Our Bodies, Ourselves.

People who came together to help each other -- even when that help included smuggling drugs.

People learning they were not just individual "patients" or "clients" (nor social workers or doctors gods), but whole human beings whose lives and health depend on each other and the heath of the world around them. People who learned how to take power to shape the world, even if just in small, local ways.

People who know that our bodies are not machines, our sexuality not mere plumbing, our lives our own to live without anyone else's permission. People who learned, even, how to help each other die. And well.

None of that would I ever want the world to give up, despite -- or perhaps because of -- what it has cost. And may still cost.

***

I felt like that even as I first knew I'd have to calculate my own life in that cost. Let me go back to that year, to 1988 -- to that night when I worried Michael Lynch by fleeing a crowded Chinese restaurant, escaping to The Toolbox.

I've told you I saw Vince there -- Vince Albone, if then Vision Vincent -- dancing with a young man and smiling him right out the door. I've said I saw only one person I knew at all well. But I didn't tell you who he was.

He was Doug Bonnell, later chair of ACT's board and rather a surprising one: he had worked for the Conservative minister of health (who himself later came out). But he was a great board chair (quite handsome too), doing his last work from a bed at Mt Sinai Hospital, where he died in 1990.

In a letter I wrote then, I told Jane about that night -- details I've already told here but one I have not: a bit of bar talk about AIDS.

- Last night at The Toolbox Doug Bonnell said: Maybe if we had handled things differently in the Seventies this wouldn't be happening. (Doug is a Tory, though a Red one.) I said: It would only have happened more slowly -- and we might not have known what we know now, about sex, about ourselves.

I told him that if I had a choice between knowing what I've been privileged to know and living to seventy without ever knowing it, I'd take knowing what I know.

I don't want to be desperate about mortality. I want to say: there it is, and the way I've found it has been full of joy and revelation and love. Anything else right now (the courage of my friends excepted) seems craven to me.

***

Rude boy: Jehovah gives us the finger. (Image courtesy of that old eroticist, Michelangelo.) |

In the Garden of Eden God planted the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil -- and then warned his charges there not to eat of it. Were they to, they'd have knowledge he hoped to hog for himself. (Old Jehovah was a rude boy: he'd made them and that trick tree merely for his sport.)

He wanted to keep them innocent -- which in truth means ignorant -- even (perhaps especially) ignorant of their own bodies. It was the serpent who gave us knowledge: one bite of forbidden fruit and Adam and Eve knew -- first of all, that they were naked.

God has been mightily pissed off ever since.

Human beings, even kicked out of Paradise, even burdened with "original sin" (god, what a concept!) -- have on the whole been glad of their knowledge, quite resisting appeals to give it up. Even for the promise of eternal life.

I've never counted on that. I'll take knowing what I have been privileged to know. Still. I hope forever: deathbed confessions, my dear, are simply too banal.

Go on to Citizenship: In the world & at work

Go back to Contents

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/sex2.htm

January 2000 / Last corrected: October 22, 2003

Rick Bébout © 2001 / rick@rbebout.com