QUEEN STREET

University Avenue to Jarvis Street

Downtown

Bright lights, big issues

(not all in stocks & bonds)

|

Dreams of grandeur

University Avenue: From bucolic boulevard to monster monoliths. (All photo links appear again below)

|

|

Transplanted history

Campbell House, 1822: hauled from the Town of York to the lawn of Canada Life.

|

|

Glory of Empire

The South African War Memorial (& other monuments to lost boys).

|

|

Halls of law & governance

Osgoode Hall (above) & Toronto's City Halls (New & Old below; two more even older).

|

|

Culture Clash

The Ward: above 1913; below 1910. The "less fortunate" fodder for the "helping professions."

|

At University Avenue we have clearly left behind the fine grain and funk (even if ersatz) of Queen West. Here, a street modest for much of its stretch goes grand, even monumental: traversing the official heart of the city; flanking the financial core of an entire (if often resentful) country.

University's broad lanes, converging to the south, head north hemming a wide median -- one of Toronto's few attempts at a formal boulevard, realized at least in scale: grim corporate and medical mausolea guard what seems a funeral route to the Ontario legislature at Queen's Park. There is no university on the Avenue, if one just west (and east) of the province's pink palace. How all that came to be you can see on a side tour.

You'll also see there dreams more grand, their shadow falling back along Queen. Canada Life's Beaux-Arts confection -- the only one of many planned (in 1929) to rise along the Avenue -- is bridged over Simcoe Street to new digs stretching west to McCaul. South sits a Greek temple clearly built in hope of a more noble setting: 1911 plans (you can see them too) would have made it the landmark terminus of a diagonal boulevard, named for King Edward VII. It was left just another branch of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, imperial vistas unswept.

|

|

Failed grandeur

CIBC branch at Queen & Simcoe, aspiring to a boulevard not to be.

Queen's southeast corner at University: vacant since the Supreme Court of Ontario went for an opera house -- yet (if ever) to be. |

Just east is a huge grey block facing University: another bank, local fortress of the Bank of Canada, circa 1955. Or so it was: its federal crest now marks the King Medical Centre, upscale offices for specialists met with unwilling notoriety: their landlords, a jet-set couple, lately jetted off with their cash.

It once had across University, if facing Queen, a near twin: the Supreme Court of Ontario. That went to plans for a grand opera house -- still just plans on the second site planned. The first, at Bay and Wellesley, fell through: it now houses a condo complex called (without evident irony) "Opera Place." It may get a twin here: both deals involved provincial land and funds, governing divas both left and right ever changing their tune. For now it features a few tree, and parked cars.

The corner does have its grace notes. University's median is marked by the South African War Memorial -- more noble than the war it recalls. Just west sits a historic house, if historically not here: Chief Justice Sir William Campbell's 1822 manse long stood far east, capping the vista up Frederick Street in the Town of York. Facing demolition, it was rescued by barristers of the 1970s, hauled from its site (left vacant for years) to shelter beneath the bulk of Canada Life.

Across the way are barristers too, there since Sir William's day. By 1829 the Law Society of Upper Canada had bought (from another chief justice) six acres northeast of what is now Queen and University -- if then Lot Street and the newly opened College Avenue. And, then, well out of town.

There they remain, their green patch preserved as the town grew around it, since 1857 (at the latest) protected by an elegant wrought iron fence. Its odd gates, legend has it, were meant to keep out cows; some suspect they were truly meant to impede intruders less placid than bucolic bovines.

Through that fence we can see (in spring, past beds of blazing tulips) the Law Society's palatial home, Osgoode Hall, named for another chief justice, Upper Canada's first: William Osgoode. There is another Osgoode Hall: the law school now at York University, long housed here in the benchers' spreading domain.

The original Osgoode Hall went up in 1829 at the head of York Street: it is still there, if now mere east wing to a complex marked on the west by a twin Georgian block built in 1844. Between them stretches a façade worthy of Versailles (if not so graced until 1857).

Newer blocks flank City Hall's square on the east, on the west up University to a modern court house. A passage beneath its suspended cylindrical chamber leads from avenue to square; its shape creates amazing echoes -- a grand if perhaps accidental practice ground for oratory.

Nathan Phillips Square, fronting Toronto's "new" City Hall, was clearly meant for oratory. Viljo Revell's flying saucer caught in a clamshell, opened in 1965, sits far back from Queen Street, its vast front yard concrete panels, not grass, and nearly devoid of impediment. With intent.

Designed for public gatherings, it became the city's true civic square -- sometimes so called (Rosedale bad boy Scott Symons titled a novel Civic Square, counterpoint to his Montreal Place d'Armes) if named for the mayor who made it happen.

It is not entirely empty. To the west squats 2.5 tons of bronze: Henry Moore's "Three Way Piece Number 2," better known as The Archer. South is a fountain pool made a skating rink in winter; on the east is a later Peace Garden. But its space is occupied mostly by people, sometimes in their thousands, a temporary stage set up for performances and (often, stage or not) political protest.

The elevated walkway framing the square -- nearly level with the landing pad of City Council's saucer (reached by a ramp sweeping up from the square), bridged to the Sheraton Centre across Queen -- harks back to dreams of pedestrians perched high over busy streets. Those heights are abandoned, often blocked off: we stayed on the ground; even (as you'll see) went underground.

Flanking the square on its east is another City Hall -- called "Old" now, the new one when it opened in 1899 if long a familiar sight even then: it took ten years to build. Its sandstone cliffs and 300-foot campanile look built to stand forever but, just 60 years later, nearly fell -- to a shopping mall.

Toronto was then much inclined to scrap the old; blackened with age, Old City Hall looked a likely sacrifice to the shiny new Eaton Centre. It was saved in 1968 by vocal citizens -- opening a new chapter in civic politics. Eaton's built around it, failing to outshine it: cleaned in the 1970s, Old City Hall proved beneath the grime a beauty of intricately carved stonework, glowing buff, ochre, even pink. It's now fading back to beige -- if unlikely to be regarded ever again as boring.

No longer a hall of governance, it remains one of law: designed as both city hall and court house, it houses court rooms still. In 1979 I got quite familiar with one, there for the six-day trial of The Body Politic -- first of three.

I was not personally under charge until the third, in 1982 and not heard here. Maybe that spared me any souring on Old City Hall's civic majesty. Its clock belfry makes my favourite city sound, rhythms set so deep in my bones I can cue each sonorous bong. I love being there at noon. Or midnight. But I need not be there: all across downtown, even beyond, we can hear the echoing hours.

The neighbourhood around these halls of law and governance was once less grand, seen even as lawless, perhaps ungovernable, at the very least dirt poor and disreputable. The photo at the left, with Old City Hall looming behind, was taken in 1913 -- on land now Nathan Phillips Square. It was then the heart of The Ward, most notorious slum in the city's history.

From 1880, The Ward was a transplanted shtetel, Jews later joined by immigrant Italians. Well into the next century, Toronto the Good saw it as a sordid mess: busy lanes crowded with hawkers, shoppers, scavengers, sleepers; affairs of all sorts shamelessly carried on in public by young and old alike -- as if foreigners didn't know enough to keep their kids (or bedrolls or even loos) at home.

Its nearby streets were a scandal: taverns, dance halls, pawn shops, vaudeville and burlesque joints; "street boys" and "problem girls" dangerously beyond parental supervision -- and "Mad for The Show." Poverty, crime, dirt, disease, and (most egregious) immorality made this nabe a prime petri dish for police, public health officials, reformers fired by passions progressively social or evangelically sacred (in practice, hard to tell apart).

Here the "helping professions," some newly born, were let loose on "those less fortunate" -- and on kids out for what little fun they could find.

|

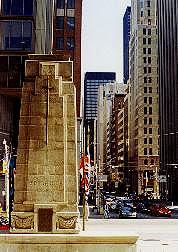

Fabled canyon

Bay Street, from behind the Cenotaph at Old City Hall. |

|

High rollers, no skates

Scotia Plaza's 68 storeys loom over John Lyle's 1949 Bank of Nova Scotia, shot from the door of the old Stock Exchange. Commerce Court rises beyond in stainless steel; below, a park bench warning in its court. |

The tower of Old City Hall looks down what poet Raymond Souster called the "fabled canyon" of Bay Street. Originally Bear Street, named (legend says) for a beast once chased down it, the street now sees more bulls than bears. At least in good times. Billions of dollars (or maybe just digits) daily change hands here.

This is Canada's capital of capital. The corners of Bay and King are bracketted by bank head offices (in effect, if one nominally in Montreal), four of Canada's Big Five. The fifth is down Bay next door to BCE Place, Bell Canada Enterprises into much more than phones. The Toronto Stock Exchange, long in an Art Deco wonder now the Design Exchange on Bay, is nearby in a tower at King and York.

|

|

|

| Towers of power: Bank of Montreal's First Canadian Place, in endless marble veneer (seen from CIBC's Commerce Court); its big blue logo, with Scotia's red next door, give us a skyline topped S & M. The Toronto Dominion Centre's black monoliths: framing a foggy CN Tower; flanking BCE Place & Royal Bank's facets of real gold. |

Stacked one floor atop the other, the office real estate within a few short blocks of Bay and King would rise nearly 1,600 storeys -- more than eight times higher than the CN Tower. The Bank of Montreal's more sensible 72 floors hold 2.5 million square feet all on its own. And some 10,000 people.

Many more cram the financial district every day -- exactly how many no one seems able to say. The Toronto Transit Commission can say that the five stations in the subway's south loop see 234,000 riders in and out each weekday.

A few are also there at night, as cleaners, maintenance workers, security guards. Yet, within that same loop, there are fewer than 500 permanent residents. In the glittering shot at the top of this page (from atop the CN Tower, on a postcard) the lights are on, but almost nobody's home.

That is due to change. But it's unlikely that any of those cleaners, guards, or even secretaries will end up finding home here.

|

|

Condomania

Promo for 1 King West on a block to go for a 51 storey tower, the 1913 bank beyond to stand swallowed: "Your own downtown pied à terre" luxury hotel style (if not many pieds: $200,000 for 300 sq ft), touted as "an investment property." The Ritz Carlton, 65 condo / hotel floors set to rise at Bay & Adelaide, courtesy of Donald Trump (& eager lapdog Mayor Mel Lastman): "From $450,000 to $18 million Cdn."

|

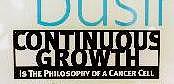

All across town, condos are rising. Rental apartments are not, almost none built in the last 20 years -- but for "Bonus Era" units subsidized by developers, buying City leave to stack more storeys onto new office towers than the Official Plan allowed (at least officially) in the 1980s.

The provincial Tories have lifted rent control on vacant units; vacancy rates barely break zero. Some 63,000 people here are on waiting lists for affordable housing. Outreach agencies estimate that 1,000 sleep on the street each night (that 1910 image above not lost history); last winter, 35 died.

Toronto's mayor has declared homelessness "a national disaster" -- yap from a lapdog of luxury. The feds hopped to with $680 million -- covering all of Canada, contingent on matching city and provincial funds (Ontario yet, if ever, to commit) and meant to be spent not now but over five years. A sop to that yap: Canada is the only major industrial nation without a national housing policy. That protest sticker above is pasted over the face of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien.

In the last three years across the country, City Councillor Jack Layton says, we are at 300 dead of homelessness. And counting. But only condos, and Donald Trump, seem to count. So far.

|

Private property; public life

The Eaton Centre & PATH: "Toronto's Downtown Walkway." Go in, go down -- go shopping!

|

Along Queen beyond Bay, we go shopping. Maybe at The Bay, filling the block all the way to Yonge Street, department store successor to Simpson's -- here from 1881 until bought out by Canada's oldest company (older than Canada itself, as a country): for the Hudson's Bay Company, selling has been good since 1670.

|

Shopping is good

|

North across Queen stood another retail empire: the T. Eaton Company. Founded by Timothy in 1869, Eaton's is no longer, bankrupted by his great grandsons. But it remains in name: the Eaton Centre, a downtown mall stretching all the way north to Dundas Street, Toronto's biggest tourist attraction.

Via the Eaton Centre -- or by portals dotting downtown posted with signs reading simply (to many tourists' befuddlement) "PATH" -- we can really get down to some shopping: underground. Or under the towers over our heads, their basement levels become malls linked beneath the streets, a maze of paths weaving 10 kilometres.

Busy as you'll find it, PATH is not, like the streets above, true public space. It just plays at it for profit -- and may stop playing if you play (rather than pay) to excess. You can wander its paths, and the Eaton Centre, on a side tour.

Shopping behind us (or nearly), we are at Toronto's famed if odd main street: Yonge. Begun in 1794 nearly four miles north as a military route to the Holland River, it reached this corner a few years later -- as a boggy trail called the Road to Yonge Street. Only in 1812 did it run south to the lake. Much later it was cut far north and west, running as Highway 11 to Rainy River, nearly in Manitoba.

Like Queen, much of Yonge has been spared redevelopment (but for stretches like the one here filled by the Eaton Centre), lined mostly with old buildings, shop fronts tucked into their street floors, the 19th century surviving above. It seems less a civic boulevard than small town main drag, a honky tonk strip -- even Sin Strip: "clean up" campaigns have long lent city fathers lots of political mileage.

|

|

|

| Yonge Street: Left: Eastbound Queen car between The Bay and the Eaton Centre, Old City Hall rising behind. Above, crossing Yonge: Eaton Centre left, far towers at Bloor, 2 km north. Right, mapped on the sidewalk at Dundas: "Yonge Street: The longest street in the world: 1,896 km." (But it's since lost the Guinness record to the Pacific Coast Highway.) |

The street is now getting a grand new square, up at Dundas -- imaginatively touted as "Toronto's Times Square." But tarty Yonge has ever confounded "world class" aspirations. It's the city's raw spine: streets are surnamed East and West from Yonge, their street numbers staring here, even on the north, odd south.

There, we have One Queen East: 26 floors of bronzed banality where once stood a finely proportioned Italian palazzo (if built by the Imperial Bank in 1914). North at 2 Queen East the garlanded classicism of a 1909 Bank of Montreal branch is being façadomized for the new Maritime Life Tower.

|

|

Queen East

1909 bank at Yonge & Queen, braced for Maritime Life's modern thrust.

Beyond, St Michael's Hospital: "Toronto's Urban Angel" spreads its latest wing 16 floors up along Victoria St. |

|

Streets of faith

Church & Bond: Metropolitan United & St Michael's Catholic (above); St James Anglican; Jews, Lutherans, Greek Orthodox -- & secular sizzlers William Lyon Mackenzie & Egerton Ryerson.

|

|

Mutual view

Unbroken Victoriana on Queen East: displayed (right) in proud miniature; above, the real thing.

|

Not far beyond Yonge downtown's towers, rising so suddenly at University Avenue, nearly fade away. Down Victoria Street another condo grows; at King and Yonge beyond stand what were once the city's tallest buildings, outranked as the gravitational centre of commerce shifted west. It ever has: the oldest part of town is still some blocks east, past Jarvis Street; we'll see it on a later tour.

At Victoria we get the west wing of St Michael's Hospital, lately risen to 16 storeys, just past on the south two modest medical office towers flanking a five-level garage. But beyond, all the way to Queen's end, the tallest towers belong to churches. One spire nearby, at 306 feet, long held the city's record. (And its clock.)

Up Bond Street, down Church, and here on Queen stand the cathedral churches of Toronto Catholicism, Anglicanism, and Methodism (if the last since 1925 united with other Protestants, so not strictly a cathedral). You can see them and more secular monuments on a side tour, streets of faith placid beside Yonge's roar.

From here Queen East has much the same feel we found along Queen West: an eclectic mix of old and not so old, trendy and tawdry, rundown and restored. Running up the east side of Church, hard by Metropolitan United, is a string of pawn shops. The odd green turret at that corner, lately an optical shop if soon to serve pizza, was the original Thrifty's -- since spawning a giant jean chain.

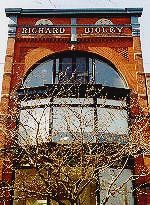

A stretch on the south is proudly restored (so proudly there's a model displayed in one of its windows): a warehouse and industrial row reaching back through the block, built in the late 19th century (the Robertson chocolate factory among them), since finding new use as the Queen Richmond Centre. In 1972 City-TV made its first home here, at 99 Queen Street East.

|

Restored (& resolutely not) Richard Bigley made his mark in 1873 at 98 Queen East, later home to TV producers. At 90-92, Blue Sea, & the late Ming's, for lease. |

That row terminates the view down Mutual Street, a view I know well: I live on Mutual, my usual route south (when not quiet Bond) to the Blue Sea and Queen beyond. I knew the corner before I lived here, doing graphic work for FUND, the Foundation to Underwrite New Drama for television, beneath the banner of Richard Bigley, 1873.

Bigley was in tinware and stoves; his building later housed produce, a tobacconist, and likely much else before television arrived. FUND has since left. But their address will surely see new uses. Queen Street always does.

See more on:

The "Bonus Era" & its accidental monument on Temperance St, in Mad for The Show.

Sources (& images) for this page: Robert Harney & Harold Troper: Immigrants: A Portrait of the Urban Experience, 1890 - 1930, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1975 (McCaul St Public School basketball champs, 1912). Yesterday's Toronto, 1870 - 1910, Prospero Books, 1997 (YWCA & street sleepers, from the James Collection, City of Toronto Archives). Toronto Reference Library Picture Collection (The Ward, 1913). Toronto Transit Commission (by phone), Jun 2001. 330 Bay Street Development Corporation (the Ritz Carlton). Barbara Neyedly: "The homelessness disaster still with us," The Toronto Voice, Dec 2001. Joe O'Connor: "Gimme shelter," Toronto Life, Jan 2002.

* For sources cited throughout, see Life on the street.

Downtown side tours (each linked to the next, in the order below):

Dreams of grandeur

University Avenue: From bucolic boulevard to monster monoliths

Glory of Empire

The South African War Memorial, & other monuments to lost boys

Halls of law & governance

Osgoode Hall & Toronto's City Halls present, past, & lost

Culture clash

The Ward, 1880-1930

Mad for The Show

Street boys & problem girls meet moral reform

Private property; public life

The Eaton Centre & PATH

Streets of faith

Church & Bond: Sizzling preachers divine & democratic

Or go back to:

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/downtown/dttour.htm

Guide to Queen Street stories & tours

My home page

November 2001 / Last revised: February 19, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com