|

Promiscuous |

|

Cheap space (with rich effects)

24 Duncan Street, 5th floor

Fronting on Adelaide, Duncan door at the back, right (a 1999 shot, the place renovated). Top floor right, with the four arched windows: TBP's initial digs; from mid 1980 the whole floor. Found by chance in 1976 (Merv Walker, Ken Popert & David Gibson shown there then) the location would see -- & shape -- much of The Body Politic's history. |

TBP's earlier history

For key players (some you'll meet in this chapter) & events from 1971 to 1974 (& a bit beyond), see:

Rick Bébout:

The Body Politic

Donald W McLeod:

Ed Jackson & Stan Persky, eds:

On the Origin of

The Body Politic

Inventory of the Records of The Body Politic & Pink Triangle Press

Canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives, 1998.

Begun in 1988 as a list of archival holdings; expanded online as a substantial source for the paper's history. It includes narratives on TBP's published work & internal workings, appendices of collective members, correspondents, key writers & volunteers -- more than 500 people in all -- & 37 images.

& Visions of Community.

A 1995 essay tracing changing notions of "community," as seen by TBP over its 15 year history, & beyond.

Lesbian & Gay Liberation in Canada:

A Selected Annotated Chronology, 1964-1975.

ECW Press & Homewood Books, Toronto, 1996.

The most thorough, fully annotated source for the period. Click on its title above for more info in the CLGA site.

Flaunting It! A Decade of Gay Journalism from The Body Politic.

Pink Triangle Press, & New Star Books, Vancouver, 1982.

An anthology of the best of the paper's first decade, including a chronology, less complete than Don McLeod's but covering seven more years -- & available online:

Victories & defeats: A gay & lesbian chronology, 1964-1982

TBP & Queen West

Rick Bébout:

Diva Diaries

An extended look at the Queen West scene TBP lucked into, as reflected in Anti Diva, the 2000 autobiography of Rough Trade's Carole Pope.

|

Beepers (Many more to come)

But love don't pay the rent:

Gooey (Gary's work not):

Big boys:

|

|

Sexist? Or just sexy?

Dudes promo, & Dudes:

|

|

The local competition

Esprit

Of 48 ads in Esprit's first 3 issues, 1/3 (& all big ones) were from baths, mostly the Club Bath Chain. The rest were from only 14 other sources. Editoral content seemed hard to get as ads. Most articles were unsigned (a hint of in house work), from sober to lifestyle (plants, 3 pgs; fashion, 3; cuisine, 5 -- your host Rick Stenhouse, partner in The Barracks). A 3 pg piece, "Baubles, bangles & big business," featured Ron Shearer, a lovely man: George Hislop's lover.

Of the first 3 issues' 206 pages, 70 were filled by chapters of US novelist Patricia Nell Warren's The Front Runner. (Reviewing Warren's next book in TBP, Gordon Montator led off saying it "is, of course, crap.") Other full pages were portfolios of sexy men (& one woman), sometimes nude, many done by Norman Hatton (you'll meet him later). Esprit folded in 1977.

New Directions; same gang:

Directions went for more beef (& more Norman Hatton, including this cover shot), 12 pages out of 44 in one issue. There was no news section (as there'd been in Esprit); there was "How to Cruise a Steam Bath," by Peter Buchove, with the Richmond St baths. Born in 1977, Directions died after five issues.

|

1977

- Sunday, January 2, 1977:

The facts of life at the moment are these: I am one of three partners in a business which occupies most of our lives, and which only one of us -- not I -- does not, at base, detest (what a sentence); I am living with a man / boy whom I am sure I love (but not so sure that I simply said, "whom I love") and who I think loves me, perhaps despite himself.

Beyond that, beyond these, I have trouble finding anything more basic, more simply my own, to report. This is what is wrong.

One dark morning I got to the store at 7 am as usual, locked the door behind me and stood there. Just stood -- and started to cry. I went and sat on the back stairs leading down to the basement and cried and cried, hard and loud. It was half an hour before I could gather myself, get up, unpack everything yet again and open that goddam door for another hateful day.

I spent what time I could get that day on the phone, looking for help. Not for the store. For my head. I found a psychiatrist covered by public health insurance at a community clinic run by the Toronto Western Hospital. I was to see her once a week.

In the middle of our fourth visit she said: "I think we're done. I knew the first day you walked in that all I had to do was listen to you talk yourself into the two things you already knew you had to do: quit your job and kick out your boyfriend."

She was right. By then I had done both.

I remember the moment with Brent, in February. He was in the tub, getting ready for another night out, scrubbing his crotch for whomever it might be. Not me.

I said: "I want you to go." "What?" "I want you to move out." "You're kidding." "No, I'm not."

He was shocked, then angry. He did go -- out that night, and soon for good. We did stay friends, if at first not easy ones. One night in April 1978 he'd join me at The Parkside, I with a group of friends, not paying him the attention he sought. He'd been down. He cried.

A few days later I'd get a letter from him. "I felt you didn't care a shit about me," he'd write, ending with: "I love you and it hurts when it seems that you don't care. Say hello some time."

I did. Brent later moved to Vancouver; on trips there I'd always visit, spending good times with him. A few years on he'd be back in Toronto, making his living as a freelance writer -- for, among other media, the very one he found me in: Toronto Life.

I see him occasionally and always marvel that, even over 40, he is just as handsome as he was at 21.

I don't recall what I said to Paul and David, though it must have been hard, fearing a long friendship at risk as I left them to the grind. Paul felt the more abandoned, by then no happier at The Upper Crust than I, if much more locked in by his relationship with David.

They had help over time, the business eventually employing a substantial crew. It became a limited company and went into wholesale -- at margins far too low. Sales doubled in its second year but profits shrank by half; by 1979 it grossed more than half a million dollars -- with a net loss of $29,000.

On July 3, 1980, Paul's 30th birthday, The Upper Crust would go bankrupt, $230,000 in debt. The last of that debt followed all three of us until we too were bankrupt. Friends who'd lent start up cash had been made shareholders, losing it all. David's mother nearly lost her house, remortgaged to back the business; Paul and David kept her housed, covering her payments for years to come.

The abandoned store was taken over by another baker. Years later I'd walk in, anonymously, and buy a loaf across the very counter we'd built. They kept the name: we'd never registered it, fearing flak from a huge conglomerate that sold one brand of its bread as "Upper Crust." I'd often see that logo I designed, by then someone else's property.

Tales of small business indeed. Paul would greet the end of The Upper Crust as his birthday present; by then even David had had enough. Both would go back, much more successfully, to the "rat race." And we did stay friends, for many years to come.

I wasn't sure what I was going to do. That's when I wrote the second résumé of my life and started looking for work. In the meantime I kept myself occupied by going back to volunteer work at the Canadian Gay Archives.

It was bigger now, in a new location: 24 Duncan Street, fifth floor, a warehouse walk up south of Queen West, where it had moved with The Body Politic in May 1976. As I sat there one day sticking clippings in a ring binder, David Gibson handed me a piece of paper, a news story, and said, "Could you edit this?" I wasn't sure: I'd been an editor once, but years before -- and what did I know about news? Nothing really. But I did it.

Soon I wrote a news story myself, on the May 9, 1977 fire that damaged Holy Trinity Church. It had been a huge blaze, worst in the city since 1904, taking out lots of buildings. I did it up big, even took pictures. After submitting it I ran into Keith Sly, editor of news with David Gibson, at The Parkside. I asked him if the story had been all right.

"Well," he said in his big, braying voice, "we had to cut it some." It ran in the June issue: a small shot of Holy Trinity with a four line caption, no byline, no photo credit. A useful lesson, I suppose.

Merv Walker was there every day. He had been since 1973, working on The Body Politic full time if unpaid until April 1976, he and Gerald Hannon the only paid staff; everyone else, collective members included, worked without pay.

Among many other tasks Merv, with David Gibson, designed and produced The Body Politic, working to an overall format done by Kirk Kelly in 1975. Merv and Gerald brought zany touches, often subtle, to what could seem a too sober effort. One of them once captioned a photo of the publisher of The Advocate, standing alone with a horse: "David Goodstein (left)."

They had most fun, as I later would, with the paper's own promo. A sub ad in the May 1977 issue led off: "Don't know where to put your head these days?" The photo was an old movie still, a forlorn woman regarding a shrunken head.

- "Vegetable crisper too small? And there hasn't been a hatbox in the house since great aunt Agatha moved to Moose Jaw? Take heart. The Body Politic is renowned for its absorbent qualities.

"Metaphorically speaking, it's not a bad place to put your head either."

But after more than four years there Merv was tired -- and poor: his pay, once he was paid, had started at just $3,600 a year. One day he said to me: "Why don't we swap jobs?" I'd left the bakery but it was looking for staff, Paul and David friends of Merv's as well. So Merv went off to bake; I took his place at the layout tables, learning from him and David Gibson, a volunteer as by then Merv was too.

Even paid staff were volunteers, really, often doing well over 40 hours a week. Sometimes twice that, or more.

By June I was one of the paid staff, Gerald Hannon the other, at $8,000 a year. In August I was voted onto the collective, joining Gerald, David, Keith, Merv, Kirk, Ed Jackson, Tim McCaskell, John Harnick, Paul Trollope, and Gary Ostrom, the paper's long time cartoonist, his work ever zany.

Keith Sly abstained in that vote, perhaps wary of my swift and rather casual induction not only onto staff but into the paper's formal centre of power. The collective met weekly, making all major decisions. Membership was solely by invitation; people were not usually asked on until they'd been around at least six months (then; the rules ever changing), giving others a chance to suss out their politics. I seemed a sudden exception.

There was some irony in Keith's concerns, quite apart from procedure. I had known him on and off since the day in 1972, I think, when Flav and I spotted him wandering in Queen's Park. Later we got to know him. I once took him home: he carried me around the apartment, my legs over his shoulders, my shoulders clutched in his hands, fucking me like mad. Keith was a big man.

He was stage manager for various theatre companies: in New Brunswick in the mid '70s, where he had founded Gay Friends of Fredericton and started sending news to The Body Politic; and at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa. I had visited him once or twice for some interesting episodes there, too.

Still, I got on well with Keith and the rest of the gang. Between endless administrivia and intense rounds of production, I even managed to get in some writing. I did three more news stories, small if not quite as small as that piece on the fire. But news was not to be my métier: in all my years at The Body Politic it would be the one area in which I did almost nothing.

In the October 1977 issue I did a review of Quentin Crisp's The Naked Civil Servant, having a good time with it, an even better time the next month doing a feature interview with Quentin Crisp himself. He admired our ancient freight elevator: "It's like being in a mine, only we're going up."

In the same issue I had a review of -- big surprise -- Marjorie Perloff's Frank O'Hara: Poet Among Painters. I was also running the paper's mail order book service, that title on offer, as were Jonathan Ned Katz's Gay American History, Kate Millett's Sita, and Jane Rule's The Young in One Another's Arms.

The only collectivists I didn't warm to were John Harnick and Paul Trollope. John, working mostly on classified ads, was soon gone. Years later he would put up a website in which he'd recount his brief and unhappy time there. Paul was a law student, serious, his background in Trotskyist politics -- not known for its charm. In time I would find Paul had some of his own.

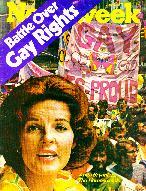

In the September issue we did a photo spread on a bunch of gay men playing ball, precursor of the Cabbagetown Group Softball League. Some of Paul's fellow Trots sent a letter scolding us for such silliness: we'd given a mere quarter page to local demos by the Coalition to Stop Anita Bryant, the orange juice evangelist who on June 7 had got Miami to overturn its gay rights ordinance.

I'd done a promo poster for that issue: "Play Ball!" over the butt of a hunky ballplayer in shorts. Paul Trollope called it "sexist." I suspected he meant merely sexual. But that was a distinction rarely made by gay leftists at the time.

That same issue saw an ad for Dudes, "Opening soon." It too stood charged of sexism, its photo two hunks, torsos only. The collective debated all such dubious ads. We usually operated by consensus, only the most fractious issues coming to a vote. The Dudes ad was accepted by a majority of one.

Such images and the style they embodied had overtaken early '70s glitter. That time's politics of polymorphous perversity, backing up androgynous display, had also faded. Now queens were outnumbered by "clones" -- satin traded for denim and leather; bijoux for studded belts and armbands; flowing locks for neat crops; languorous, ethereal bodies for big butch pumped up ones. The gym was a new gay shrine.

The buff butch look was so pervasive that it was soon an object of parody: "You know the guy I mean," ran a cartoon caption in New York's Christopher Street, "the one with the short hair and moustache."

Moustaches became such potent signifiers that people would write about them in TBP as erotic even when abstracted from the body. One found himself turned on by a mere brush of hair on a display card. In time most men at the paper had one. (And keep them to this day -- more a mark of generational solidarity among those of a certain age than a means of erotic allure: a lot of younger gay men don't like them at all.)

Some saw this new gay masculinity as simply a matter of style -- as if choice of style were not at some level a matter of substance. Others, taking that point, called it "oppressor identified." But clones were not merely aping straight men. The look could carry an element of conscious parody -- for those who wore it most consciously. To paraphrase a line we'll hear later, they were not trying to look like men; they were dressing up as gay men.

And, my dear, few straight men ever looked so good.

This was to be the look of Dudes. Open by late September in a laneway off Breadalbane Street just behind The Parkside, it was the first new gay bar in Toronto since 1973.

At first it wasn't quite a bar, unlicensed and allowed to sell only low alcohol beer, promoting itself as "A near bar nearby." And, for the first time in this town, the owners were gay: Roger Wilkes, a founder of the York University Homophile Association in 1970, and his partner David Payne.

The place looked like an upscale rec room, the walls done in diagonal slats of light wood with mirrors in place of some panels. There was a pool table, a bar that in time would serve real booze, and a raised, railed off area with tables for eating by day, cleared off for dancing by night.

At coat check you could buy coloured hankies coded to a wide range of erotic tastes, further clarified by the wearer's choice of hanging one from his left or right back pocket. A chart explained them all, further codifying -- one might say abstracting, even confining -- the definition of the modern homosexual.

Among a series of random words in Dudes' first ad were: jocks, moustaches, cruising, hot, raunch, and graffiti. Its washroom was rumoured active; hype, I suspected, so on my first night there I tested it, taking handsome Jerry Fogg (an old boyfriend of Robbie's) into the can and, the coast clear, coaxing him into a stall and sucking his very nice cock. He was a bit surprised, but he did come.

Dudes became very popular.

The Body Politic wasn't the only game in town when it came to gay publishing. With its insistent politics, disdain for the ghetto, and limited appeal to advertisers, it seemed the perfect mark for competetion by those who might take a lighter "lifestyle" approach. And some tried.

Suprisingly, they didn't succeed. Or perhaps -- given what they produced -- not surprisingly. Most efforts were connected to gay businesses, patricularly the baths, also their main advertisers.

They tried to go glossy, but often the only gloss they could afford was the cover. If that. Up against full colour US competition like Torso, Mandate and Blueboy, photo spreads of hot men weren't quite so hot (even if excellent shots by Norman Hatton) when in black and white on dull matte stock.

In many US cities tavern guilds and business associations became powerful players in local gay politics. That never happened in Toronto: they didn't have the bucks; never made their customers into a constituency. As Ed Jackson once said, local gay business types were a very petite bourgeoisie.

They also never had TBP's secret (well, not so secret) ingredient: the passion of hundreds of people willing to work not for a boss but for themselves, for each other -- and for free.

The Body Politic, by the time I got there, was already a veteran of some notable adventures. In its fifth issue in 1972, the paper had published a piece called "Of men and little boys," Gerald Hannon daring to suggest there that some interactions, even erotic ones, between older and younger people might not automatically be abusive.

A columnist for The Globe and Mail claimed TBP was the house organ of CHAT, which had got some small federal employment grants -- and thus that government money was being used to "promote the seduction of children."

The paper had been housed at the CHAT Centre; in the ensuing panic it was evicted. A later Globe editorial suggested Gerald's article could be construed as counselling to commit a criminal act. The police had been asked "whether action would be taken against the newspaper or its author." None was. Then.

In 1975, a Sergeant Banford of the morality squad had shown up at the 93 Carlton Street office, pulling from his briefcase a copy of the paper's May issue. Inside was a full page, 15 panel cartoon called "The Continuing Adventures of Harold Hedd." In four of the panels Harold and his equally Hedd hippie boyfriend were in joyful 69, complete with splurshing cum.

There had been no complaints, Sergeant Banford said, "but this comic strip won't do. Kids are coming in off the street and buying this." He ordered every copy taken off the stands. Having no choice short of an obscenity charge, the collective complied.

The next issue's cover was one of the blowjob frames, a black lightning slash reading "Toronto Morality Squad" obscuring the dirty bits. Or meant to: you could see through it. Another press run had to be ordered to clean it up. The sergeant got in touch and warned, "If you do this again, we'll seize it and charge you and close you down."

"A day without orange juice

Kiddie porn?

|

|

"Come from the raid?"

"A dinner out of Chekhov":

|

Trials without end

(TBP's -- & too many others)

The Dec 30, 1977 police raid led to nearly six years in court -- years of bath raid & censorship trials too. See:

Victories & defeats, the online chronology from Flaunting It!, tracks case details to mid 1982. But there's much beyond.

Rick Bébout:

Even in 2003, "Men loving boys loving men" lingers on. See:

The Trials of The Body Politic.

Among other trials. This record is spotty, rushed into shape for a later adventure (with odd echoes of "Men loving boys loving men"): Gerald Hannon's "Kid-sex hooker prof" mess with Ryerson Polytechnic University. See 1995: Oct - Dec.

Text crimes

It was laid out early that summer and stood ready to go, but the collective debated it for six months. The time did not seem right. In June Anita Bryant had played the " molester" card to great effect, her Miami campaign called "Save Our Children." In July a 12 year old shoeshine boy had been found dead on the roof of a Yonge Street "body rub" parlour. Four men were charged for his murder, one of them gay. The media screamed "homosexual orgy slaying."

So long as kids & sex, however linked, remained a hot button issue (forever, maybe?), the time would never be right, never perfectly safe. But, we realized, we'd never been into playing it safe.

"Men loving boys loving men" ran in Issue 39, the last of 1977, one of three pieces on the year's themes: Miami, Media, and Children, the cover flagged "The Year" with no mention of the article. It had been redesigned, Ostrom giving it a big man and a small boy in silhouette (both based on big men: those September softball players), throwing a frisbee and with them a little dog too. On November 21, it hit the stands.

On December 22, Toronto Sun columnist Claire Hoy finally noticed, heading his usual rant (where he'd already called gay people "scum," "creatures," and "fags") with: "Our taxes help promote abuse of children." A familiar line, though this time The Body Politic actually had got some government bucks: two annual grants from the Ontario Arts Council, all of $1,500 each -- maybe two percent of our entire budget. But hey: "taxpayers' money" is always a grabber.

On Christmas Hoy hit again: "Kids, not rights, is [sic] their craving." Two days later The Sun ran an editorial titled "Bawdy Politics" (not the last time they'd use the line) and streeters asking people to opine on "recent articles [sic] in a homosexual publication that advocated the seduction of children."

On the 28th The Globe reported that Ontario's attorney general Roy McMurtry was "appalled" by the article -- "as described in news reports."

On the morning of December 30 The Sun ran a story saying the York Crown Attorney was, on the advice of the morality squad, considering charges. The headline: "Crown to study sex mag."

Not a few gay men wished it were a sex mag. They were ever disappointed.

Needless to say, we had a rather tense holiday season. Kirk Kelly, usually in Montreal, was in town for it all. Kirk was generally a brazen sort but I remember him, on the subway as it happened, very nervous: when will the boot come down on our heads?

Still, we carried on much as usual. On the afternoon of Friday, December 30 Michael Lynch, Bill Lewis, David Gibson, Jonathan Katz and I left the office to catch the 4:45 ferry to Ward's Island, for dinner with Michael Riordon.

Michael Lynch, originally from North Carolina, taught English at the University of Toronto. He'd been with the paper since 1973 and had done only a brief stint on the collective but -- like other noncollective regulars, if none more so than Michael -- he was hugely influential in The Body Politic's life, then and later.

In the September issue he had profiled Bill Lewis, a key activist in Winnipeg, now here in Toronto, Michael's lover, and writing for TBP. Michael Riordon, author and playwright, had done a regular column, "Flaunting It," since 1976. Jonathan Katz, noted New York gay historian, was in town to see David Gibson; on an earlier visit they'd become boyfriends. (They still are.)

Michael Riordon ushered us out of the cold into his little cottage with an odd greeting (I can relate this because Michael Lynch later wrote it down, giving his piece that greeting as its name): "Come from the raid?"

Michael had news we'd just missed being part of: at 5 pm, five plainclothes cops had trudged up the five flights of 24 Duncan, warrant in hand, and started taking the place apart.

We called the office and got Ed Jackson. The warrant, he said, cited Section 164 of the Criminal Code: use of the mails to distribute "immoral, indecent, scurrilous or obscene" material: The Body Politic, Issue 39.

The cops were carting off everything: financial records, files from every cabinet including those in the Archives, unopened mail, editorial material for the next issue, and -- most frighteningly -- subscription lists. They might, it was hinted, even cart off Eddie and Tim McCaskell, the only other collective member there.

Ed said not to come back until the police had left. So we ate, on edge. Michael Lynch said it felt like a dinner out of Chekhov: all the important action happening off stage. Jonathan Katz said in self parody, "This is gay history!" It would be, perhaps more so than even he could imagine.

At 8 pm we called back, the cops still there but also a reporter from The Globe and Clayton Ruby, the well known criminal lawyer we had called when things first started to heat up. He had called the attorney general's office, saying that if we were told exactly what the police were looking for we'd gladly turn it over. His offer was refused. They wanted everything.

"We'll close you down" was suddenly a haunting echo.

Out on the Island, over dessert, we checked ferry times: there was one back to the city in 10 minutes, the next in 50. We gobbled fast and rushed out.

Back at 24 Duncan we were surprised to find the place not a mess. Ed said the police had been neat, jovial, even ordering in sandwiches. But they had left with 12 crates of stuff. Others arrived: Keith, Gerald, Ken. We looked around, checked files and drawers, all a bit in shock.

On a whim I looked under our big shipping table and found two long boxes: the computer cards for the subscription list -- so we still had a copy! Maybe we weren't dead. I shouted out my find. Keith snapped: "Shut up!" -- suspecting the place was bugged. We never knew for sure, but he was likely right: the phone taps were often obvious enough.

I wish I could end this story here. But I cannot: its primary plot would not be resolved until October 1983, a final subplot fizzling out only in April 1985. Welcome to the world of radical publishing.

|

Domestic politics

48 Simpson Avenue:

|

Techno politics

The Body Politic lived through a revolution in technology -- & in its political use. Before the '70s typesetting equipment, based on hot metal (melted lead), was huge, complex, expensive -- & thus limited to big companies. In less than a decade all that changed -- then changed again.

TBP bought its first typesetter in early 1977: a Compugraphic 4, at $35,000. A lot of money -- but not so much that small operations couldn't, for the first time, have type capacity in their own hands. We used the Comp 4 not only to do TBP but books, movement flyers, briefs, brochures & -- as PinkType, a commercial service to help finance the machine -- other people's mags, most small & radical.

In 1980 we got a Compugraphic 7500, able for the first time to store copy on floppy disks (first I'd ever seen; 8 inch ones). The next generation came a few years later (at $100,000): two terminals; on screen page assembly. In 1982 we also got our own photostat camera.

All this hardware is now long obsolete, replaced by desktop publishing on Macs & PCs costing just a few thousand bucks -- & thus in many more hands.

Within a month I packed off to 423 Sherbourne, just a short hop south, a house cut up into tiny apartments. Very tiny. But it would do for the moment: I meant to keep looking, didn't even unpack everything.

In December Merv told me about a place at 43 Simpson Avenue, across the Don in Riverdale. He knew the owner, wife of a man whose company had typeset TBP. It was spacious if odd, up in the roof of a small house. The bedroom's gable peak was so low you could stand up only in the middle. There was no bathroom, one on the second floor shared by the tenants. I shaved at -- and sometimes peed in -- the kitchen sink. Still, it was charming enough.

One tenant was Gay Bell, a tall laconic lesbian who did political performance art. I came to know her well, less at home than at the paper, where she was often at its own typesetting machine, bought in early 1977. Across at 48 Simpson were Merv and Ed Jackson, a couple these past four years, Gerald and his lover Robert Trow, Herb Spiers, and Billy Sutherland -- all caught up in the life of the paper. Herb was one of its 15 founding members, the only one left; Ed and Gerald there since the second issue in 1972; Merv and Robert by 1973. From the middle of 1977 Billy, training to be a nurse, was also at that typesetter.

Number 48 was the BP collective house -- one of many such abodes at the time, group households a breeding ground of budding gay activists as people refined their politics at home as well as out in the world.

There, as at the office, the precise definition of "collective" shifted over time. So had the address and membership of this particular menage: Paul Macdonald had been with the gang, less Billy, at 38 Marchmount Road, where for a while the paper was laid out in the basement. So much of The Body Politic's political clout had been concentrated under that one roof that people involved but not living there (Michael Lynch for one) came to call it inhabitants the "kitchen collective."

I'd be at 48 Simpson often, if not a kitchen collectivist. Gerald and I, paid to be at the office all the time, were the seed of a budding group that would also be accused of usurping too much power: the "staff collective."

So, even by domestic proximity I was moving deeper into the life of the paper. The streetcar trip to and from downtown, more than nine kilometres (we were metric now; about five and a half miles), became part of that life, too, if any of the 48 Simpson gang were along for the ride.

I recall Eddie and I, after trips home, standing for a half hour or more outside our respective houses, going on and on and always about the paper. The Body Politic consumed our lives. And that was just as we would have it: nothing else could possibly be so exciting.

Go on to 1978

Go back to: Contents page / My Home Page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1977.htm

December 1999 / Last revised: October 22, 2003

Rick Bébout © 1999-2003 / rick@rbebout.com